Beginnings

James Brindley, the engineer of the Trent

and Mersey Canal, was a giant of the

canal age. He had a vision of connecting

the four main rivers of England (Trent,

Mersey, Severn and Thames) in an

ambitious scheme known as the Grand

Cross. This canal was part of that scheme

and was also known as the Grand Trunk

canal.

James Brindley, the great canal engineer. The first of his

towering achievements to fire the imagination of the age was

his aqueduct near Manchester, which carried a canal ‘as high

as the tree tops’ over the River Irwell.

Image reproduced courtesy of the Institution of Civil Engineers

Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery designer and

manufacturer based in Stoke-on-Trent, saw how a canal

could be a vital route for the transport of his wares.

Canals offered a smooth ride for his pottery, which could

otherwise be easily broken. He was present at the

momentous meeting at Wolseley Bridge, just outside

Rugeley, where the canal was planned in 1765. It was

opened fully in 1777.

The canal helped to raise the profile of Rugeley and

greatly benefited the trades and industries of the town.

It had cost approximately £300,000 to build (equivalent to over 27 million

pounds today) but was nevertheless a good investment, as carriage costs

were reduced by over two thirds. It cost nine shillings (45p) to transport a ton

by road and two shillings and sixpence (12.5p) by canal.

The murder of Christina Collins

On 15 June, 1839, Christina Collins began her

journey as a passenger on a freight-carrying

narrowboat from Liverpool. Her intended

destination was London, where her husband had

gone to look for work. She never got there. Her

body was found in the canal at Brindley Bank near

Rugeley aqueduct, about a mile from here. Two of

the crew of boatmen with whom she had shared

her journey were later convicted of her murder.

The story was used by the author of the Inspector

Morse novels, Colin Dexter, in ‘The Wench is

Dead’.

These steps, known locally as the Bloody Steps,

are at Brindley Bank, just outside Rugeley. It was

here that Christina Collins’ body was carried after

being found in the canal. Some said that her

blood had dripped on the steps and stained them,

giving rise to the local legend: the ‘Bloody Steps’.

Nearly 10,000 people attended the

hanging of James Owen and George

Thomas in Stafford for the murder of

Christina Collins. This broadsheet

shows the portable gallows that was

wheeled out of the gaol gatehouse

into Gaol Road to enable the public

to view the hanging.

|

From commerce to leisure

The development of the railway network in the mid 1800s brought a cheaper and quicker method of transporting goods and presented canals with a serious threat. In 1846 the Trent and Mersey Canal Company merged with the North Staffordshire Railway Company, but by the 1860s the canal had lost much of its business. The next hundred years saw the canal struggling to recover and a steady decline in commercial traffic. Today, under the control of British Waterways, leisure use has grown and traffic is mostly recreational.

A boatman and his family on the Trent and Mersey Canal at Rugeley, c1890–1900. Horses were used to draw the narrowboats, and could transport up to one hundred times more weight on water than on land.

Image courtesy of Staffordshire Arts & Museum Service

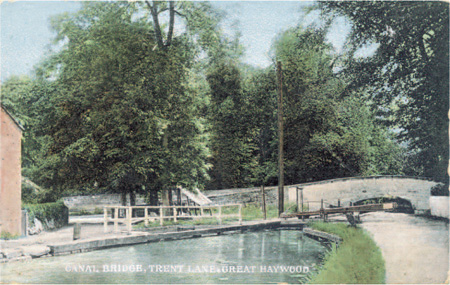

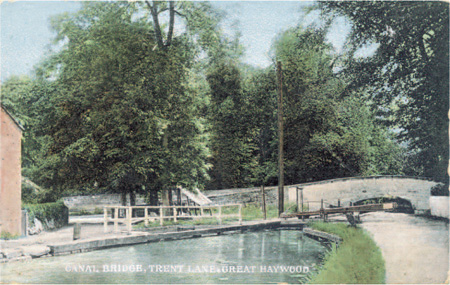

Spot the differences

These two photographs,

taken one hundred years

apart, show the same spot

on the canal, at Trent Lane

about four miles from Great

Haywood. The lock-keeper’s

house, seen in the earlier

photograph, still stands.

The narrowboats seen on

the canal now are more

likely to be pleasure boats

than the industrial

transporters of a hundred

years ago.

1908

Image courtesy of Staffordshire

Arts & Museum Service

2008

The junction of the Trent and Mersey Canal and the Staffordshire and

Worcestershire Canal at Great Haywood. Construction of both canals was

granted by Act of Parliament on the same day.

|